Impressionism in Normandy: The Sites that Inspired Monet

ÉTRETAT

As I walk beneath the limestone giants, the swoosh of the incoming tide also threatens to knock me off my feet and, with the briny breeze tousling my hair, I can’t help but wonder how Monet et al stood still long enough to capture this incredible scene on canvas. Once I return to the boardwalk above the beach and gaze out across the dazzling white sea, I can appreciate it more fully.

Back in 1885, when Monet painted the scene, a small information board tells me there were little red-sailed sardine fishing boats bobbing in the wash, but today a number of black-clad surfers are waiting to catch some waves, and no doubt enjoy the views at the same time.

While the beach and boardwalk offer sensational up-close views of the cliffs (if you can stay standing!), to really enjoy their drama, it is best to walk the no doubt enjoy the view at the same time. up path that leads to the clifftops. From here, on top of the first of the three iconic arches, you can see the beach and cliffs in panorama – the Chapelle Notre-Dame de la Garde perched on high in the distance. It’s a wonderful sight, and little wonder Monet was so taken with this stretch of coastline that he painted it dozens of times, depicting various hours of the day, the fishermen and the changing nature of the sea.

For those wanting more information, the tourist office offers an audio walking tour, and there is also a series of panels placed along the Seine-Maritime departement’s coastline highlighting the different places in which the artists stood with their palettes and canvas.

Ricardo Isotton on Unsplash

GIVERNY

While Etretat is by far the most impressive natural location among the Impressionist sites, when it comes to naming the most iconic, it must be Giverny, Monet’s garden. This house and garden was the residence of the artist from 1883 until his death in 1926, and it provides a wonderful insight into his life and work.

Arriving on a misty morning, and dodging the raindrops, I meet my guide, who leads me into the Clos Normand part of the garden through a small green door in its periphery walls. As I follow her along the narrow paths, she explains that Monet intended part of the garden to represent a paint palette with different flower beds planted in one colour.

When we enter the house, again it is the colour that strikes you. Many of the rooms are decorated in only one colour, such as the bright yellow kitchen, the heart of the house. Elsewhere, I’m fascinated to learn that Monet was an avid collector of Japanese art, which was fashionable at the time (the most celebrated art work being Hokusai’s The Wine), which explains more fully his desire to create the Japanese water garden.

Elsewhere in the house we come to his studio, which has been re-created from photographs to look almost identical to how it was in Monet’s day, albeit with copies of the paintings that now hang in the world’s most famous galleries, in among the paintings are photographs of his two sons, and his adopted family that came as a result of his second marriage to Alice Hoschede, whose own daughter Blanche married Monet’s eldest son Jean.

Blanche was something of an artist herself, and her paintings are strikingly similar to Monet’s. A copy of her 1889 work Haystack hangs in what was once her bedroom. Following the deaths of both Alice and Jean, Blanche returned to Giverny to care for Claude Monet as his sight deteriorated, and she remained there until her own death in 1947.

The Japanese water garden is separate to the house and to reach it, we crossed the road, the route of which used to be a railway, I was from the train, en route between Paris and the coast, that Monet first spotted the Giverny house, before going on to rent and then buy it. The water garden itself is, even in inclement weather, something to behold.

While Monet’s paintings are etched on most France-lovers brains, to see the real inspiration is a special moment, and even more so once you hear how it was developed out of marshland. Streams were diverted to create the ponds, and Monet came up against local farmers who believed the exotic plants, brought from the east, would poison livestock. As we wander around the garden, peeking through the trees and flowers at the famous green bridge, it feels every bit the haven of peace that Monet intended.

LE HAVRE

The town of Le Havre could not be more different from how it was in the late 19th century, when Monet painted the sun rising through its industrial chimneys. The bombings during World War II devastated the town, and its post war concrete architecture designed by Auguste Perret became a World Heritage site in 2005. It’s a curious place, but no less inspiring for its neat streets and uniform buildings.

On the seafront, the striking MuMa Musée d’Art Moderne André Malraux is built in steel and glass, with a hold sculpture named “the signal” outside. Inside, it is intended to resemble a boar, with ramps between levels giving the feel of gangways, and complete with a busty figurehead hanging above the doorway looking out to sea.

While much of the art is modern, the museum also has an impressive collection of Impressionist works, from Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Edouard Manet, Alfred Sisley and Camille Pissarro. This is thanks in no small part to a donation from Hélène Senn-Foulds, the granddaughter of art collector Olivier Senn, which means that MuMa has one of the largest collections of Impressionist art in France. The gallery is a superb showcase for the paintings, with its bright, modern spaces, allowing you to enjoy the light (on a sunny day, at least) that so entranced these artists.

For me, the highlight was the entire wall of large and small artworks from Eugene Boudin over the mezzanine level. The small gold frames complement the paintings beautifully, and it was a pleasure to walk along, glancing into each little window to another world with bright blue skies, coastal scenes and harbour views.

HONFLEUR

The highlight of Honfleur is its colourful old harbour and the tall, narrow buildings, their bright awnings reflecting in the water. It is a setting I have seen hundreds of times, but vicariously through photographs and, while I knew it was pretty, I didn’t realise how striking it would be. As I count the windows to see how many storeys there are – eight- my guide Anne Marie explains that each house is not one residence, but two; the lower part of the building has its entrance on the harbour-front, and the upper part is accessed from the street behind.

Yet however striking, it was the boats that were more of a muse to Monet, along with the smaller back streets and the wooden church. The Eglise Sainte- Catherine is France’s biggest surviving timber-built church, and was crafted by shipbuilders after the original stone church was destroyed by the English during the Hundred Years War. It was only intended to be temporary, but it is still standing more than 500 years later. Its belfry was built separately; so the vibration of the bells wouldn’t shake the church, or to avoid sparks from a lightning strike on the tower setting fire to the church, according to another theory. Despite its size, the interior of the church is wonderfully cosy, with a Christmassy air to it. The pillars around the oak trunks sit on the original cone bases, while the roof is shaped like an upturned hull of a ship.

Honfleur was the home of Eugène Boudin, who was born in the town in 1824. It was his paintings that I had so admired in Le Havre, and a museum dedicated to his life and works is a short stroll from the church in Honfleur. He was known as the ‘king of the skies’ for his dramatic landscapes, and he had a big influence on the young Monet. Inside, a good selection of his work is on display as well as works from the post-Impressionist era, from artists including Fernand Herbo and Henri de Saint-Delis. Away from the paintings, a stunning picture window allows you to gaze out towards the impressive modern bridge, the Pont de Normandie.

ROUEN

From the window of an underwear shop, which is now Rouen’s tourist office, Monet painted some 30 impressions of the cathedral at all times of day and year, and in all weathers. It was a fascinating study in the impact of light on the same subject matter and was challenging even for Monet. By that stage (the 1890s) Monet was established in his career – though not revered enough for the ladies in the underwear shop not to object to his presence and the task led him to have nightmares. “Things don’t advance very steadily,’ he wrote to his wife, “primarily because each day I discover something I hadn’t seen the day before… In the end, I am trying to do the impossible.”

Not being a religious man, it wasn’t the subject matter that most enthralled him, but the play of light on the Gothic facade. Monet entered the cathedral only once, and as I walk into the space, I can’t help thinking that his nerves would have been calmed by doing so, such is the tranquil nature of its interior.

One of Monet’s paintings of the cathedral – Le Portail et la Tour d’Albane, Temps Gris – hangs in the city’s Musée des Beaux-Arts, which has a fantastic collection of art, including other works by Monet, as well as by Pissarro, Sisley and Renoir. When my guide and I stand in front of Sisley’s 1893 Chemin Montant au Soleil, I am captivated by the painting and its glorious sunshine. It proves that, whatever the weather outside, there is always a bright scene to admire somewhere in Normandy.

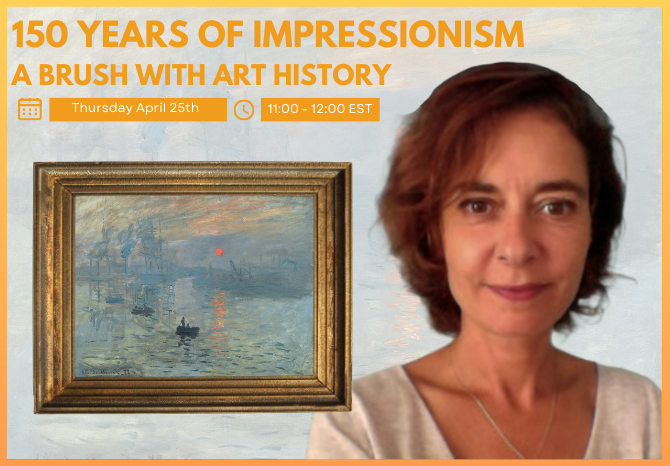

Join France Today on Thursday, 25th April

The first Impressionist exhibition in Paris in 1874 unleashed a tectonic shift in art history. To celebrate this milestone, France Today are thrilled to present an online event featuring esteemed speaker Anne Catherine Abecassis, a leading expert in the field with a doctorate in art history from the Sorbonne University who specializes in French painting of the 19th and 20th centuries. Her deep knowledge and passion for the subject make her the perfect guide to explore why this revolutionary movement which was first met with confusion and criticism, went on to be universally acclaimed. Reserve your spot now!

Looking for more on Normandy?

The latest issue of France Today magazine plots a gentle driving tour of Normandy’s stunning inland areas (think colombage houses, cider routes and cheese tastings) – you can see a beautiful Rouen facade on the cover:

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

More in french art, impressionism, Normandy