In the footsteps of Pierre-Auguste Renoir

Travel with Mark Stratton as he discovers the places which inspired the incredible French Impressionist and the amazing legacy he has left behind

When Pierre-Auguste Renoir laid down his palette one final time just over 100 years ago in December 1919, he was France’s most celebrated artist, bequeathing humanity masterpieces that today create hushed reverence and auction for staggeringly high prices. Marking the centenary of his death, I travelled around France tracing where he lived, loved, and painted. My companion for the trip is Barbara Ehrlich-White’s astonishingly detailed Renoir: An Intimate Biography, which draws upon 2,000 letters from and about him.

Paris

I began in Pars, in Montmartre’s bohemian neighbourhood where Renoir rented poor accommodation and studios in Sacre-Coeur’s shadows. He lived a rootless existence in near poverty, relying on the patronage and handouts of wealthy patrons.

By the mid-1870s, his style was evolving. His figures gained greater clarity of form while maintaining his ethereal dappled backdrops. His studio at 12-14 Rue Cortot is now within Musée de Montmartre, where I began my Renoirian odyssey. Originally a 17th-century house, the museum is a stone’s throw from a lively area of cabaret and guinguettes (open-air dance halls) that young Renoir loved to frequent. The museum’s exotically scented gardens of blooming roses reveal exactly where he created several of his greatest masterpieces including La Balançoire (The Swing, 1876) painted upon the lawn where a replica swing still dangles.

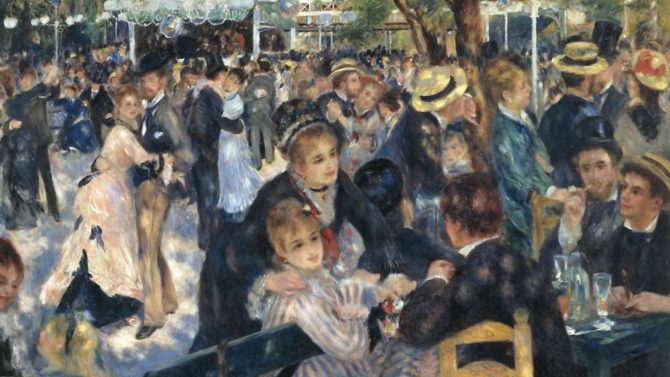

By now he’d had a child called Jeanne with his first model, Lise Tréhot, before beginning another affair with his new model, Aline Charigot. This relationship, according to Ehrlich-White, coincided with his greatest ‘romantic masterpieces’. One such masterpiece was conceived a short walk from the museum. Bal du moulin de la Galette (1876) captures a guinguette full of couples dancing and friends drinking in Sunday finery; so-named after one of Montmartre’s famous old windmills. Today the spot is represented by a replica windmill beneath which is a bistro. Driven by his unceasing perfectionism Renoir painted two versions between 1874-6. One, a smaller canvas, sold for $78m at Sotheby’s in New York in 1990 to a private collection. The larger canvas, however, hangs in the fabulous Musée d’Orsay where several dozen of his masterpieces hang on the fifth floor, alongside those of his friend, Cézanne.

Renoir’s other tour de force is Luncheon of the Boating Party painted around 1880-1: another guinguette with friends sharing wine and conversation on a balcony edge. It displays his confident maturing towards more classical realism in the characters’ faces, particularly Aline’s, painted in a flowery bonnet kissing a small dog. This masterpiece resides overseas, but from Châtelet-Les Halles I hopped onto the RER A-line west to Chatou to locate where it was conceived. Today Maison Fournaise remains a restaurant with a bijou museum attached. Renoir frequented here between 1868-85 painting the countryside and Parisians’ riverside pleasures. From the riverside below I recognise the terrace’s curved cobalt-blue railings and faded red-and-white canopy from the painting.

In Paris I mopped up other masterpieces. At the Louvre, then later at the magnificent Musée de l’Orangerie where there is a magnificent collection of 145 Impressionist pieces bequeathed by collector Paul Guillaume featuring four decades of Renoir. Seen side-by-side his evolution throughout is striking; almost like different painters. From his early wraithlike abstraction in Paysage de neige (1870s) to Nude woman lying down (1906) depicting a classicism inspired during visits to Italy where he admired Raphael and Pompeian frescos.

Essoyes, Aube

Great changes were afoot by the late 1880s during the next phase of his life. He’d acquired financial security enabling him to marry Aline in 1890 and they reared three boys: Pierre, Jean (the famous film director), and Claude, known as Coco.

Aline was from Essoyes in beautiful Aube. Increasingly, with his new family in tow, Renoir came to Essoyes to paint, at first renting until able to afford an extravagant townhouse. Essoyes remains dominated by Renoir’s presence.

“I want to buy a Renoir for the village but it’s hard finding something less than €7million,” laughed Françoise Tellier of the Renoir centre in Essoyes. An interesting trail visits locations pertaining to his work including a large mural picturing his masterpiece, Gabrielle and Jean (1895), marking the residence of Gabrielle Renard, who aged 15 came to work in their household around 1894.

The art trail leads to the house Renoir bought and painted in between 1897-1916; nowadays a funky little museum, sold to the local municipality by his descendent Sophie Renoir. Mixing original furnishings and that of Renoir’s era, the museum fosters a delightful snapshot of domestic normality. The living room is scattered with toys, his messy easel, plus a piano to entertain guests.

Like Renoir, Aline is buried a few hundred metres away in Essoyes cemetery, their remains committed in individual tombs. While Aline is interred with her mother and Coco, Renoir lays with his older sons, Pierre and Jean. His tomb topped with a bronze bust, sculpted under his supervision in collaboration with Richard Guino. Girona-born Guino had been Renoir’s assistant in his final years.

South of France

Following medical advice from around 1898 Renoir would spend increasingly more time in southern France’s warmer climes usually separate from Aline. By the early 1900s his fame was such he was made a Chevalier de la Légion d’honneur by the state. I made the long rail journey south to the Côte d’Azur to trace the final chapter of his life. The sun kisses my face stepping from the rail station of Cagnes-sur-Mer, a small coastal town of 58,000 inhabitants.

I visit Renoir’s magnificent second home, Les Collettes, now a museum in the suburbs. With Mediterranean views, the farmstead is set amid eight hectares of olive trees planted in 1538 by Francis I. But in 1907 he built a new larger modern house for 35,000 francs largely, Ehrlich-White suggests, to suit Aline’s haute-bourgeoisie pretentions. Yet Renoir remained ambivalent to fame.”this will not keep me from continuing my daily grind as if nothing happened,” she quotes him saying. That he did and when his rheumatic paralysis abated, he painted feverishly; his brushstrokes less refined, yet still classical in execution. He infused ever more sensuality into his art.

Renoir’s last few years in deteriorating health were stressful. Two sons were wounded in World War I, and his contemporaries, all barring Monet, passed away. When he died peacefully at home in December 1919 aged 78 he left behind 720 paintings in Paris, Cagnes-sur-Mer and Essoyes.

Numerous retrospectives continued after his death as his fame burgeoned but is remarkable rise is perhaps encapsulated in an event shortly before his death. The frail Renoir visited the Louvre. This same working-class man who’d struggled financially and critically for the first 25 years of his life was now feted when wheeled through the Louvre to see his hung Madame Georges Charpentier (1878): an exceptional honour for a living artist to be displayed. His transformation from humble artisan’s son to one of France’s greatest artists, a remarkable journey of perseverance and brilliance, was complete.

You might also like

8 famous paintings of France and their real-life inspirations

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

More in Alsace-Champagne-Ardenne-Lorraine