Mystical Places: Exploring Chartres Labyrinth in France

The latest Inspired Traveller’s Guide investigates magical destinations around the globe, including the ambitious labyrinth at Chartres Cathedral in Eure-et-Loir

CHARTRES LABYRINTH

Where? Centre-Val-de-Loire, France

What? Medieval church-floor maze, designed to bring the faithful closer to God

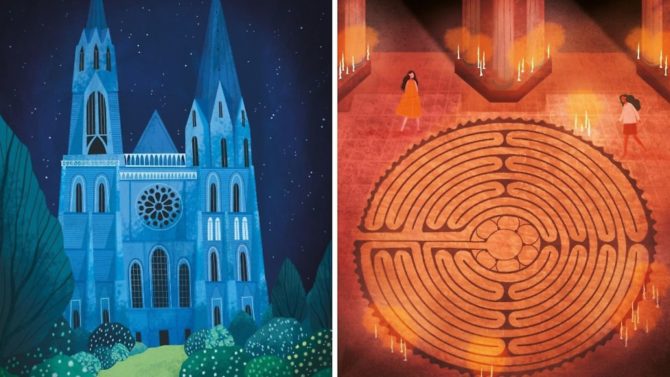

This glorious house of God can be seen from miles away, its roof lofty, its buttresses flying, its spires reaching high to the heavens – a physical and stylistic climax of early French Gothic design. Inside too, it’s a marvel of cross-ribbed vaults, soaring pillars and exquisite stained glass. But while most eyes are drawn upwards – as, in cathedrals, they’re wont to do – spare a moment to look down. For the floor tiles hold their own mystique: coiled in the centre of the nave is a labyrinth, laid in well-worn tiles, marking the long and twisting path towards salvation…

Labyrinths have existed for around 4,000 years, their winding, geometric patterns found painted into walls, carved into rocks, woven into baskets and engraved into coins since Neolithic times. While the medium might have varied, the classical design was largely the same: a pathway leading circuitously from edge to centre, with – unlike mazes – no choices to make along the way; once inside the labyrinth, the only course is to keep going, no matter how meandering, and trust you will be led to the end.

Most famous is the Ancient Greek labyrinth of Knossos, in which the bullish Minotaur was defeated by heroic Theseus; in which good conquers evil. It’s a story of overcoming fear, finding redemption – a narrative that later appealed to the Christian faith. So the pagan symbol was incorporated into Christianity: Theseus equals Jesus; the Minotaur is Satan; the labyrinth is a representation of each person’s journey through the world in search of God.

In the ninth century, things became more complicated. A monk by the name of Otfried of Weissenburg modified the classical seven-circuit labyrinth pattern by adding four extra layers. This 11-loop style became the blueprint for a slew of medieval mazes that were built across Europe – and few were greater than the labyrinth at Chartres.

It’s thought that a church has stood in this city in north-west France since as early as the fourth century, though rampaging Vikings destroyed everything in 858. In 876, the Sancta Camisa – the tunic worn by Mary at the birth of Jesus – was bequeathed to the church, and Chartres became an important pilgrimage centre. The city’s current edifice, also known as Notre-Dame de Chartres and now a UNESCO World Heritage Site, was first begun in 1145, with a remit to be broader, taller and brighter than any church that had gone before. Part of this design, installed at some point in the early 13th century, was a labyrinth of equally ambitious proportions.

Chartres’ labyrinth is not ornate but it’s elegant. It’s also big, measuring almost 13 metres (42 feet) across, the largest church labyrinth constructed during the period. It comprises a rounded design of 11 concentric circles, divided into four quadrants and encircled by an outer ring of scalloped shapes or lunations – said to represent the number of days in a lunar cycle. In the centre is a six-petalled rose symbolising union with God, and seemingly mirroring the rose window in the north facade, which depicts the Last Judgement. If walked in full, from entrance to middle via every twist and turn, the labyrinth covers a distance of about 260 metres (860 feet). And it was intended to be walked, providing a delineated space for mindful reflection and spiritual pilgrimage – a symbolic journey to Jerusalem.

On most days chairs obscure the cathedral floor. But each Friday from Lent until All Saints’ Day, the chairs are cleared away and the labyrinth is revealed, enabling silent, contemplative walking. The physical path is the same for every pilgrim – twisting, inevitable. But the thoughts it provokes are the individual’s alone. Progressing through a labyrinth, following a set way in a bounded space, is to abandon the need for external decisions, to concentrate instead on balance and breathing and to give in to the religious or mystical, to meditate on human existence. In the confines of the labyrinth, the walker is forced into confrontation with themselves.

Extracted from Mystical Places by Sarah Baxter, White Lion Publishing, £14.99.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

You might also like

7 majestic Gothic cathedrals to visit in France

Lonely Planet reveals the most unmissable travel experiences in France

Quiz: How well do you know France’s UNESCO World Heritage Sites?

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email