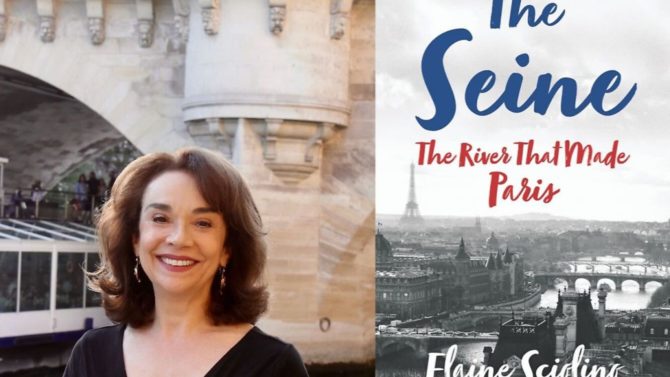

INTERVIEW: Elaine Sciolino, author of The Seine: The River that Made Paris

Former New York Times Paris bureau chief Sciolino tells FRANCE Magazine about her latest book, a love letter to the Seine – all 483 miles of it!

Elaine Sciolino is an author and former New York Times Paris bureau chief who has lived in France since 2002. Her previous books include The Only Street in Paris: Life on the Rue des Martyrs, an NYT bestseller. In The Seine: The River that Made Paris, she traces the enchanting river’s path from its humble beginnings in Burgundy all the way to Le Havre, with a special focus on the City of Light.

FRANCE Magazine: What was the most fascinating thing you learned about the Seine in your research?

Elaine Sciolino: I discovered a goddess! A Gallo-Roman proto-feminist healing goddess named Sequana. She was the star of an ancient temple that was built at the source of the Seine. Pilgrims came from as far as the Mediterranean and what is now the English Channel to pray to her for a cure, consult the pagan priests, stay for a short visit, give thanks. They threw votive offerings in wood, stone and bronze into a healing pool.

At the Musée Archéologique in Dijon I fell in love with her in the form of a nineteen-inch, two-thousand-year-old bronze statue. She stands elegant in a boat, her head inclined, her forearms outstretched as if in a gesture of welcome. The prow of her boat is the head of a duck that holds a round object—a pomegranate perhaps—in its long bill; the stern is the duck’s upswept tail. Slim and small-breasted, Sequana wears a flowing dress that exposes her forearms and part of her chest and falls in pleats to the floor. A large, broad crown partially covers her wavy hair, which is parted in the middle and tied at the back of her neck. She is young, with large eyes and refined features, and wears a look of anticipation. The museum’s curator, calls her “our Mona Lisa.”

A fictionalized eighteenth-century story about Sequana turned her into a survivor who escaped the clutches of Neptune by transforming herself into the Seine River. (The Seine was initially called Sequana.) The story is woven into the ancient Greek myth of Persephone who succumbs to Hades and must spend much of her life trapped in the underworld. But unlike Persephone, who fell victim to her abductor, Sequana escapes!

A related source of fascination was the source of the Seine itself. It is hard to find. GPS and cell phone service go dead in that forgotten corner of Burgundy. Except for warnings of deer crossings, few signposts dot the back roads that wind through farm fields and tree-covered valleys. You have to drive along a narrow tree-lined road until you come to a sign that reads, “City of Paris, Domaine of the Sources of the Seine.”

The source, believe it or not, is part of the city of Paris. In 1864 Napoléon III bought the springs and the surrounding land, built a park, planted fir trees, and declared it part of Paris, sort of a disconnected arrondissement. With a budget of about €25,000 a year, Paris pays to mow the lawns, clear the trash, repair the paths, and cut down dead trees at a site that few Parisians visit. But it’s a lovely place to have a picnic in a secluded ten-acre park with its picnic tables and benches.

You can also see the source of the Seine bubbling up in several places from underground. There is a grotto that shelters a graceless stone sculpture of a nymph and a modern sculpture, an imagining of what the goddess Sequana might have looked like. The remnants of her vast temple complex sit behind a fenced-in area.

FM: Which of the characters that you met along the way did you find the most interesting?

ES: One very strong character is Arlète Renau, who had been a bargewomen, as strong, tough, and

resilient as her bargeman husband. She welcomed me into her home even though I was a “lady of the land.” Her family had lived and worked on the river for years and were it not for the arrival of the Germans in 1940, who seized the barge to use as a tank transporter, Arlète would have surely been born on the river like her ancestors. Arlète spent her childhood on the family boat, teaching herself to read and write; her father thought school was a waste of time. Unable to speak proper French, she was mocked by people on land. She was the product of a unique and insular part of French culture, working an arduous and dangerous job. Arlète recalled how she adored that life, watching her kids take over the boat as their own personal playground, making sandcastles on the deck. Things fell apart for her when she divorced her abusive husband and was forced to live on land because of the debt she incurred trying to manage a barge on her own. Since then, she said, she has felt like “a bird in a cage,” locked away from the river she called home.

Another character I love is Darius Khondji, a world-famous French-Iranian cinematographer who filmed Woody Allen’s Midnight in Paris. He joined me for a stroll one day along the Seine at the Quai Malaquais, in the Sixth Arrondissement. We walked down a cobblestoned ramp at Port des Saints- Pères and went east, under the Pont des Arts and the Pont Neuf, which crosses the Île de la Cité. The path along the Seine there is narrow, uneven, and little used by pedestrians, except for the occasional lost tourist. His enthusiasm and passion about the light were contagious!

“I love this,” he said. “It’s all poplars. The light of the sky penetrating the trees turns the water green! And look— the trees make shadows on the stones.” As we walked, Notre- Dame appeared in all its glory, perfectly framed beyond a curved arch of the Pont Saint- Michel. “You don’t have this view with the Thames, or the Hudson, or the Tiber, or the Danube, or the Guadalquivir,” he said. “You don’t have it with any other river in the world.”

FM: The book is interspersed with references to all the authors, from de Maupassant to Hemingway, who have made Paris – and indeed the Seine – a character in their work. What is your favourite literary depiction of Paris and why?

ES: Well, you cannot avoid Hemingway and A Moveable Feast, his memoir of Paris life in the 1920s. It sounds like such a cliché, but he has to be mentioned. What struck me is not his sweeping generalizations about life in the city of light, but his passages about fishing in the Seine. He walked along the banks when he had finished work for the day or needed to “think something out.” He liked to take the stairs under the Pont Neuf to the Vert- Galant, the spit of land below the bridge. There, the Seine’s currents and backwaters created excellent places to fish, he wrote. And there, he discovered the fishermen. They fell into two categories: retirees on small pensions that could become worthless with inflation and enthusiasts who fished in their spare time. The fishermen “used long jointed cane poles,” he wrote, with fine lines, light gear, and quill floats. Sure, there was better fishingoutside of Paris, but they always caught something.

The Seine was polluted in Hemingway’s time, but the fishermen considered the fish healthy enough to eat. The river brought forth a plentiful supply of fingerling fish they called goujon. “They were delicious fried whole, and I could eat a plateful,” Hemingway wrote. “They were plump and sweet- fleshed with a finer flavor than fresh sardines even, and were not at all oily, and we ate them bones and all.”

Hemingway made excuses for why he stayed on the sidelines: he didn’t have the tackle; he preferred to fish in Spain; he never knew when he would finish work. In Paris, his fishing pleasure came vicariously. “It always made me happy that there were men fishing in the city itself, having sound, serious fishing and taking a few fritures home to their families,” he wrote.

FM: What is your favourite painting or photograph of the Seine and why?

ES: You can’t have just one favorite painting about the Seine, when there are so many, over so many years, to capture your spirit and take your breath away. There is one that is A favorite, though. Unlike so many paintings of the river that depict its water glistening in morning light, Le Pont-Neuf, la nuit captures its night magic. Albert Marquet painted it between 1935 and 1939 from his apartment on a quay facing the Pont Neuf and the Île de la Cité. The sky and water are black; the bridge and the cars crossing it shimmer in the glow of yellow and red electric lights. To the north, the ten-story, turn-of-the-twentieth-century department store La Samaritaine reigns over the scene.

Marquet didn’t write about the importance of the Seine in his work, but Monet certainly did. Listen to this: The Seine! I painted it all my life, at all hours, in all seasons, from Paris to the sea . . . I never tired of it: it is for me always new. . . . I built myself a studio in a boat. It was a sort of quite large cabin: one could sleep there. I lived there, with my material, spying on the effects of the light from one dusk to another.

As for singling out one photograph, well, there are thousands and thousands of famous photographs of the river. The black-and-white photo on the cover of my book, by Peter Turnley, a former colleague from Newsweek magazine, is brilliant.

Allow me to say I’m particularly proud of a photo I took myself, and that is printed in the book. I was at the start of a cruise of the Seine and we saw in front of us the quarter- scale replica of the Statue of Liberty that sits on Île aux Cygnes in the Seine with the he Eiffel Tower in the background. I had never seen Paris from this glorious perspective. And the two mismatched structures fit elegantly into an iPhone photo frame, which empowered even a photographically challenged person like me. I crowded with other passengers at the front of the deck and snapped the postcard- perfect image!

FM: What is your favourite riverside café, restaurant or bar in Paris and why?

ES: I confess. My favourite café, Le Dream Café, is on the Rues des Martyrs. It is not close to the Seine. But I wrote a book about the street, which I called The Only Street in Paris: Life on the Rue des Martyrs. Some mornings, I sit at a small sidewalk table there. The television is usually on, tuned to an all-news channel. One of the butchers on the street may show up holding a half baguette with ham for his first break at 10. The fromagerie owner from across the street, always picks up espressos in small cups to take back for him and his wife. Momo, the morning manager serves the best café crème on the street in heavy porcelain cups and saucers stamped “Cafés Richard.” The croissants and baguettes were made early this morning at the bakery next door.

My favourite restaurant on the Seine? Well, it happens to be one of the most expensive in Paris, Guy Savoy in the Hotel de la Monnaie, the Paris Mint. What a joy to look out at the Seine through the windows of Savoy’s restaurant. I’m lucky enough to have known Guy Savoy for years. The restaurant is way too expensive for me, but every morning the staff meets up in the kitchen for a huge buffet breakfast, which they prepare, and I sometimes get invited. The river and great food — not a bad way to start the day.

FM: Now you’ve explored the Seine, are there any other French waterways that you can see yourself writing in such depth about?

ES: The Seine is in a class by itself. It is the most romantic river in the world. After writing a book about it, I can’t see myself focusing in depth on any other French waterway. Maybe another book set in Paris. I’ve written about the gardens of Paris, the churches of Paris, the bridges of Paris. I’ve written a whole book on one street in Paris. I’m sure there will be another literary adventure, but it will not be on another river!

FM: What is your favourite part of living in Paris?

ES: I love being a flâneuse (a female flaneur or aimless wanderer) in Paris, a city of eternal discovery that never disappoints. Paris is a comfortable city of visual delights, slightly smaller than the Bronx and much smaller than London, Berlin, Madrid or Rome. It can be walked from one end to the other in hours. It is sliced by the Seine, with anchors like the Eiffel Tower and Sacré-Coeur, and that makes it a hard place to get lost, at least for long.

I once wrote this sentence for a story in The New York Times: “The streets belong to those who walk, no map in hand, no fixed destination in mind.” One of my daughters and her boyfriend found it printed on a tote bag in a shop in Brooklyn! You have to be open to anything that crosses your path in Paris. That’s why there is never any end to adventure in Paris.

I became a serious flâneuse when I fell madly, passionately, obsessively in love with the half-mile Rue des Martyrs in my Paris neighborhood. I was swept away by its spirit, feeling giddy when I strolled up and down the street at random hours of the day or night. I embraced its rhythm, which began when street sweepers opened valves that sent rivers of water downhill along the gutters and ended well after midnight with the closing of the bars and the cross-dresser cabaret. I took that same spirit with me when I travelled along the entire 483-mile-long Seine River.

FM: And what is the biggest challenge about living in Paris you’ve faced so far?

ES: It has been to learn how to understand the codes and overcome the barriers of French bureaucracy in work and life. So much of daily life is set up as obstacles, engineered as barriers to reaching your goals. You have to learn to seduce (verbally that is), which is why I wrote an earlier book about looking at France through the prism of seduction!

FM: If you could only recommend one place in Paris to visitors who want to experience a true taste of the capital, off the typical tourist radar, where would it be and why?

ES: This is my best advice: just walk and wander. Leave the security and surety of Google Maps behind. Avoid the lines at the Louvre and the Musée D’Orsay. Make a list of the wonderful small free museums the city has to offer, and then visit a few. The churches and gardens of Paris also can become your playgrounds, and they are free.

FM: Aside from Paris, what are your favourite parts of France? Could you see yourself writing a book about areas or aspects of France?

ES: For many summers, I went to the Ile de Ré with my family. An island off the coast of La Rochelle, it has everything you want out of a summer vacation. No need for a car; you just hop on your bike and ride through the salt marshes until you reach the ocean. I want to preserve the island’s serenity. I’d never write about it for a mass American audience!

FM: How did you feel on the night of 15 April when the Notre-Dame was alight? What are your hopes for the future of the cathedral?

ES: I happened to be in New York City the night of the fire and watched American television as the tragedy unfolded. As Notre-Dame burned out of control for hours, as its roof collapsed and its spire fell, the horror of the loss was mourned around the world. Some American television commentators were quick to declare the monument dead.

But I had covered war and many terrorist attacks as a journalist. I also rejoiced that no one had died, and that the fire had not been caused by an act of terrorism. And Notre Dame is a silent survivor. It took most of the 12th and 13th centuries to build, and the result was an amalgam of different styles of gothic architecture. Since then, it has weathered desecrations, renovations and violent upheavals. The most dramatic was the anticlericalism following France’s 1789 revolution that stripped churches like Notre Dame of their wealth, transforming them into “temples of reason” in the service of the new secular republic. Notre Dame was so badly damaged and desecrated that by the end of the 18th century, radicals were calling for its demolition.

I know that Notre Dame will reemerge different, of course. It will remain both a beautiful museum for the masses and a vibrant part of the everyday lives of its community, a place of music, ritual, and prayer where babies are baptized, believers attend Mass and the dead are mourned. I have no doubt that Notre dame will emerge stronger. And as heretical as this may sound today—even more beautiful than it was before.

Elaine’s book, The Seine: The River that Made Paris, will be released on 5 November (16.99, WW Norton) – get your copy here.

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email